DETERMINANTS

OF HEALTH

PROBLEM

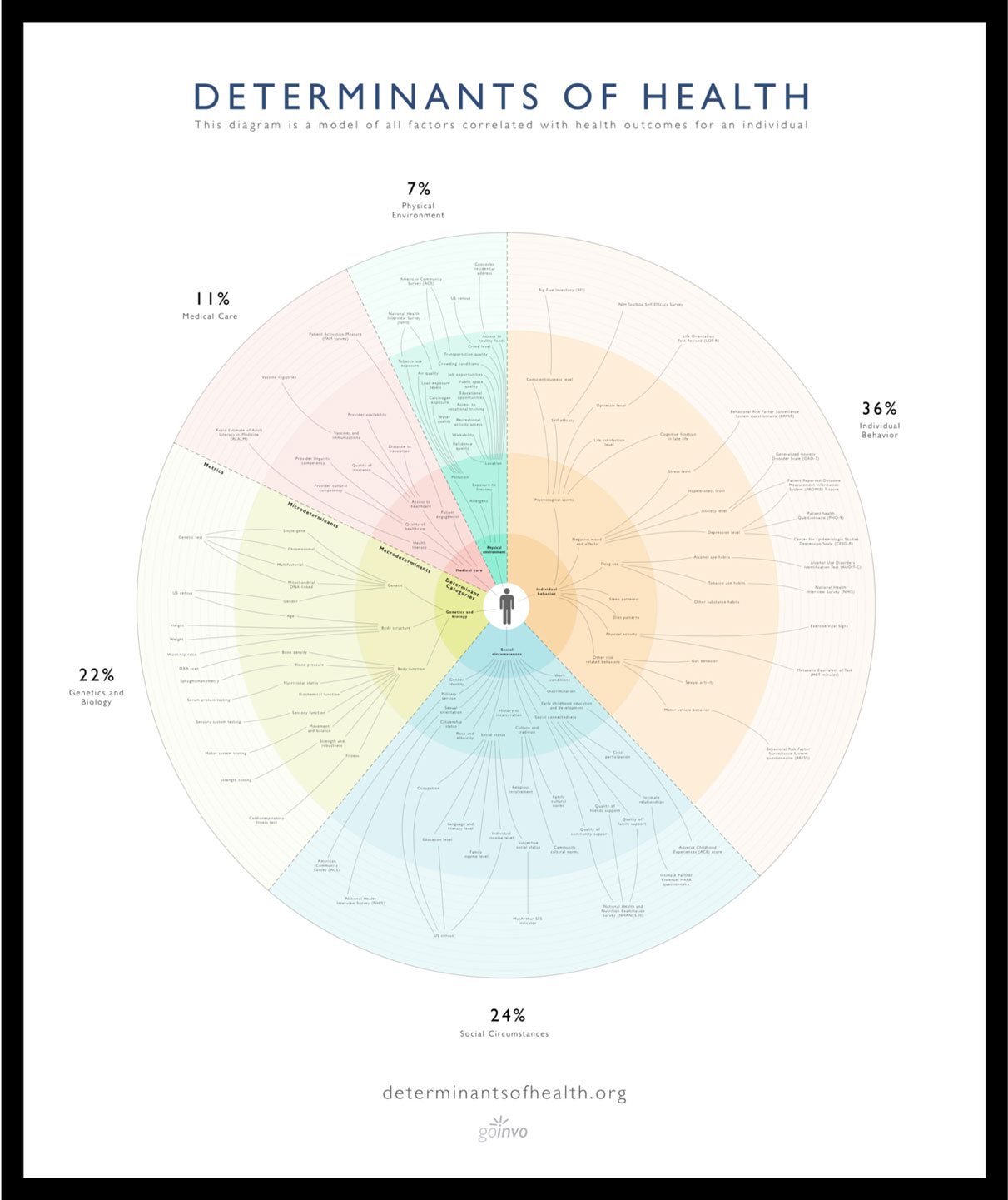

Clinical care, the focus of our health systems, only account for 11% of our overall health. However, it is necessary to view health as a holistic measure of an individual's entire living situation and life experience. These factors that strongly affect an individuals overall quality of health are the determinants of health.

Extending far beyond medical care, these factors can be used to improve health within the clinical, population, and public health spaces.

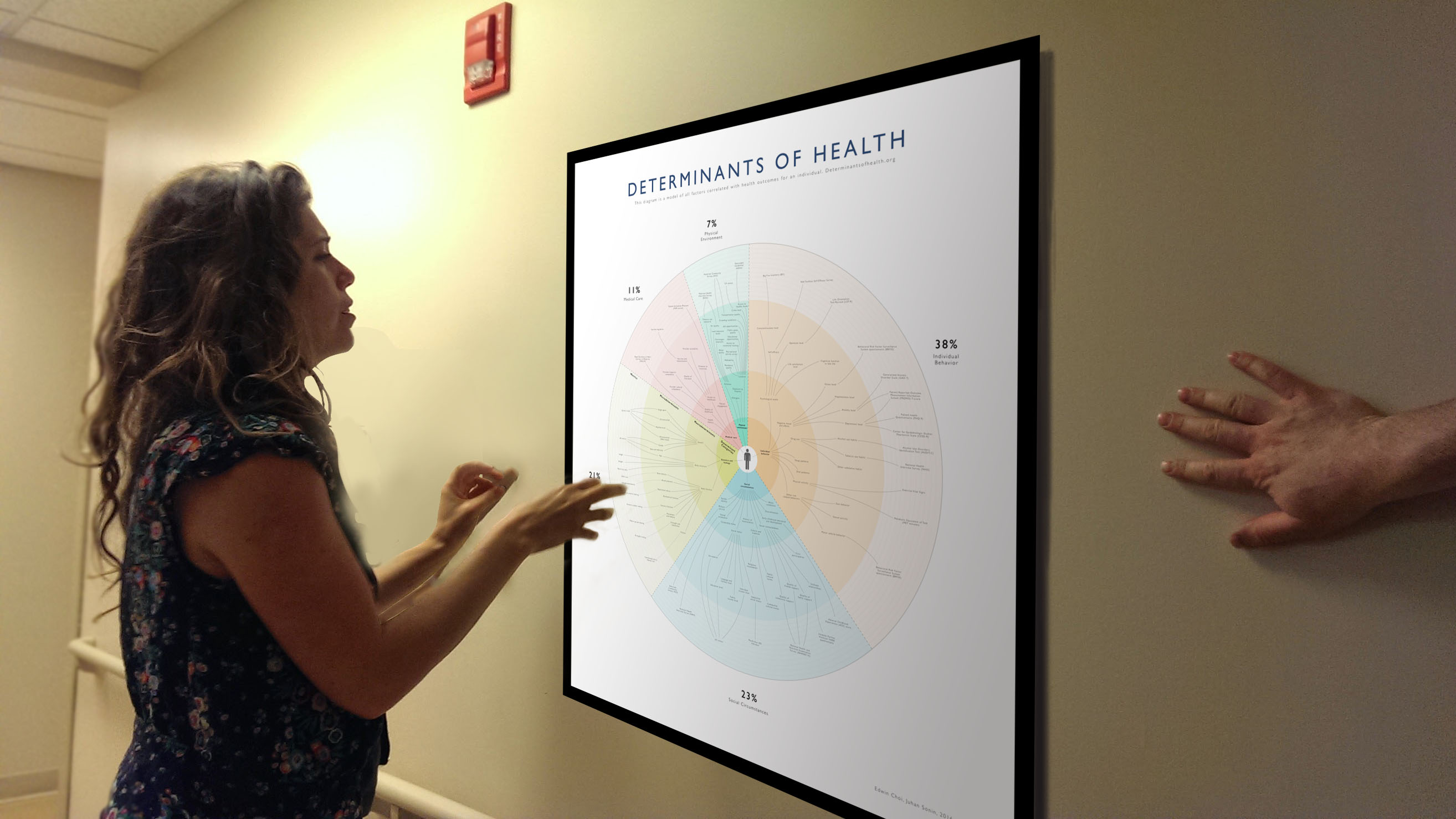

The Determinants of Health is available as a poster, an installation, a download, and an interactive visualization.

Order printDownload poster

View project on github

HOW CAN WE USE THE DETERMINANTS?

Individualized health care

Better understanding our own health, combined with giving care providers the right, available data and knowledge around a much broader set of health determinants, is the prescription for improved care and a healthier life.

Standard health record

In the US there is currently no national standardized health record (SHR). Among the health records that do exist, they are primarily focused on storing clinical information. Using the determinants of health as a guide, an SHR that views health in a holistic way can give patients and care providers the right information for successful care.

Population health

While our care starts with us, thanks to internet technologies we also have access to big data sets that provide insight for other people and communities. Not only does this enable more targeted public health interventions and policies, it provides the framework for following trends and even predicting outcomes on a large scale. Beyond having a transformative effect at a social level it can improve our own individualized health care.

Research and data access

The implementation of the determinants of health paired with the creation of the standard health record (SHR) would result in a massive breadth of health data that would empower clinicians, patients, and researchers to discover new relationships between our determinants and our health and redefine the very notion of medical care to the benefit of all.

REFERENCES

- NCHHSTP Social Determinants of Health. (2014). Retrieved March 14, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/socialdeterminants/definitions.html

- The determinants of health. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2016, from http://www.who.int/hia/evidence/doh/en/

- Social Determinants of Health. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2016, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

- Beyond Health Care: The Role of Social Determinants in Promoting Health and Health Equity. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2016, from http://kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/

- Schroeder, S. A. (2007). We Can Do Better — Improving the Health of the American People. New England Journal of Medicine N Engl J Med,357(12), 1221-1228.

- The Relative Contribution of Multiple Determinants to Health Outcomes. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2016, from http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_123.pdf

- Capturing social and behavioral domains and measures in electronic health records: Phase 2. (2014). Washington D.C.: The National Academies Press.

- Gruszin, S., & Jorm, L. (2010, December). Public Health Classifications Project (Rep.). Retrieved March 15, 2016, from New South Wales Department of Health website: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/hsnsw/Publications/classifications-project.pdf

- DHHS, Public Health Service. “Ten Leading Causes of Death in the United States.” Atlanta (GA): Bureau of State Services, July 1980

- J.M.McGinnis and W.H.Foege. “Actual Causes of Death in the United States.” JAMA 270, No. 18 (1993):2207-12

- J.M.McGinnis et al, “The Case for More Active Policy Attention to Health Promotion.” Health Affairs 21, no.2 (2002):78-93

- A.Mokdad et al. “Actual Causes of Death in the United States 2000.” JAMA 291, no.10 (2004):1238-45

- G.Danaei et al, “The Preventable Cuases of Death in the United States: Comparative Risk Assessment of Dietary, Lifestyle, and Metabolic Risk Factors.” PLoS Medicine 6, no. 4 (2009):e1000058

- World Health Organization, Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks, Geneva: WHO, 2009

- B. Booske et al., “Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health.” County Health Rankings Working Paper. Madison (WI): University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2010

- Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G., & Siegel, S. D. (2005). STRESS AND HEALTH: Psychological, Behavioral, and Biological Determinants. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 607-628. Retrieved March 16, 2016, from http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_dat=cr_pub=pubmed&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&journalCode=clinpsy

METHODOLOGY

Below is a description of the methodology used in creating the Determinants of Health visualization. It is also a record of versioned updates to the methodology and visualization based on continuing research and feedback. Thank you to those who have reached out and helped identify areas to improve.

v1 - 26.Jul.2017

The 5 main determinants of health (genetics, medical care, social circumstances, environment, and individual behavior) were chosen due to their consistency across the following 7 out of 8 organizations:

- NCHHSTP [1]

- WHO [2]

- Healthy People [3]

- Kaiser Family Foundation [4]

- NEJM [5]

- Health Affairs [6]

- Institute of Medicine [7]

- New South Wales Department of Health [8]

The lists of determinants published from each of the previously mentioned organizations were compiled and compared [1 - 8]. There was no standard in terms of the number of determinants, hierarchical organization of the determinants, and the naming for the determinants (for example, quality of housing [3] vs residence quality [7]). The most thorough publication for the determinants came from the Institute of Medicine report [7]. Therefore this was the primary source from which the list of 95 determinants within the visualization originated.

The section below documents our analysis of the data and how we calculated the final impact percentages for the 5 main categories of determinants.

The relative contribution of each of the determinant categories to one’s health was found using the estimated values referenced by the seven primary sources listed below.

- DHHS [9]

- JAMA [10, 12]

- Health Affairs [11]

- PLoS [13]

- WHO [14]

- U.Wisconsin [15]

Each determinant category was then averaged based on the values from each of the aforementioned sources (the methodology in the primary sources were different depending on the source. The final percentages should therefore be an estimate and not be viewed as absolute numbers).

Behavior: (50 + 38 + 40 + 39 + 36 + 45 + 30) / 7 = 39.71*

Social: (15 + 40) / 2 = 27.5

Genetics: (20 + 30) / 2 = 25

Medical care: (10 + 10 + 20) / 3 = 13.33

Environment: (20 + 7 + 5 + 5.4 + 3 + 10) / 6 = 8.4

*An original miscalculation of 'Behavior' has been rectified. The following values have subsequently been updated.

The ratio for each determinant was then found by taking the average values found for each of the determinant categories and dividing them by the total determinant value.

Behavior: 39.71 / 113.94 = 34.85%

Social: 27.5 / 113.94 = 24.14%

Genetics: 25 / 113.94 = 21.94%

Medical care: 13.33 / 113.94 = 11.70%

Environment: 8.4 / 113.94 = 7.37%

Total: 34.85 + 24.14 + 21.94 + 11.70 + 7.37 = 100%

The final percentages are as follows.

Behavioral determinants at 35%.

Social determinants at 24%.

Genetic determinants at 22%.

Medical care determinants at 12%.

Environmental determinants at 7%.

v2 - 30.Aug.2017

The following are updated calculations for the relative contributions of each of the determinant categories. The relative contribution of each of the determinant categories to one’s health was found using the values referenced from the six sources listed below.

- DHHS [9]

- JAMA [10, 12]

- Health Affairs [11]

- WHO [14]

- U. Wisconsin [15]

Each determinant category value is an average based on adding the values from each of the aforementioned sources.

Behavior: (50% [9] + 42% [10] + 40% [11] + 45% [12] + 30% [15]) / 5 = 41.4%

Social: (15% [11] + 40% [15]) / 2 = 27.5%

Genetics: (20% [9] + 30% [11]) / 2 = 25%

Medical care: (10% [9] + 10% [11] + 20% [15]) / 3 = 13.33...%

Environment: (20% [9] + 3% [10] + 5% [11] + 3.9% [14] + 10% [15]) / 5 = 8.38%

Additional notes on the determinant category values: For source [10], The environmental value of ~3% was based on dividing toxic agent deaths (60,000 deaths. Toxic agents were defined as occupational hazards, environmental pollutants, contaminants of food and water supplies, and components of commercial products) divided by total deaths for that year (2,120,000).

The average values found for each of the determinant categories were each divided by the total determinant value.

Total value: 41.4% + 27.5% + 25% + 13.33...% + 8.38% = 115.6133

Behavior: 41.4% / 115.6133... = 35.81%

Social: 27.5% / 115.6133... = 23.79%

Genetics: 25% / 115.6133... = 21.62%

Medical care: 13.33...% / 115.6133... = 11.53%

Environment: 8.38% / 115.6133... = 7%

The final percentages are as follows.

Behavioral determinants at 36%.

Social determinants at 24%.

Genetic determinants at 22%.

Medical care determinants at 11% (rounded down).

Environmental determinants at 7%.

ADDITIONAL CHANGES

14.Feb.2018

-

Race and ethnicity have been removed from the biology section due to a lack of standard objective criteria in the scientific community surrounding the use of genetics to define race and ethnicity. It has been added to the Social Circumstance section due to its continued social importance in describing groups based on similar characteristics. View the following literature for additional detail:

- Fujimura, J. H., & Rajagopalan, R. (2010). Different differences: The use of ‘genetic ancestry’ versus race in biomedical human genetic research. Social Studies of Science, 41(1), 5-30. doi:10.1177/0306312710379170

- Long, J. C., & Kittles, R. A. (2003). Human Genetic Diversity and the Nonexistence of Biological Races. Human Biology, 75(4), 449-471. doi:10.1353/hub.2003.0058

- AR, T. (2013). Biological races in humans. [Abstract]. Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci, 262-271. Retrieved February 14, 2018, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23684745.

- Caprio, S., Daniels, S. R., Drewnowski, A., Kaufman, F. R., Palinkas, L. A., Rosenbloom, A. L., . . . Kirkman, M. S. (2008). Influence of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture on Childhood Obesity: Implications for Prevention and Treatment. Obesity, 16(12), 2566-2577. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.398

- Discrimination can be further subdivided into racial, ethnic, gender, sexuality, and age based discrimination.

- Poster images have been updated based on the updated Aug 2017 calculations.

AUTHORS

GoInvo

Edwin Choi

Edwin is a biologist turned designer. Combining the sciences and art, he orchestrates healthcare software experiences to be beautiful and clinically refined. Edwin joined Invo in 2015, is a graduate of University of Washington, and has a masters in biomedical design from Johns Hopkins University.

GoInvo

Hrothgar

Hrothgar is a designer and engineer. Trained as a mathematician, he combines elegance and rigor in software development and interface design. Hrothgar is a graduate of Rice University, and joined Invo in 2016 following doctoral studies at the University of Oxford.

GoInvo, MIT

Juhan Sonin

Juhan specialized in software design and system engineering. He operates, and is the director of, GoInvo. He has worked at Apple, National Center for Supercomputing Applications, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and MITRE. Juhan co-founded Invo Boston in 2009 and is a graduate of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He currently lectures at MIT.

CONTRIBUTORS

Dartmouth College

Kelsey Kittleson

Kelsey is a designer and engineer. She specializes in taking an analytical approach to problem solving while focusing on human needs. She is currently studying engineering with a concentration in human-centered design and product development at Dartmouth College.

Copyright © 2016 GoInvo LLC | Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution v3